A new direction for cancer research

In collaboration with the University Hospital Basel, researchers from ETH Zurich in Basel are investigating the early stages of bladder cancer. Their findings show that future research should also focus on mechanical changes in tumour tissue.

Dagmar Iber is Professor of Computational Biology at ETH’s Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering in Basel. Her research group uses a combination of lab experiments and computer modelling to investigate how cells organise themselves into organs and other complex, three-dimensional tissue structures based on the genetic information they contain. Until recently, their work did not touch on cancer research. But that all changed when the ETH Board issued a call for research proposals combining basic and medical research on new topics in health-related fields.

In response, Iber teamed up with two professors from the University Hospital Basel, urologist Cyrill Rentsch and pathologist Lukas Bubendorf. They were seeking to understand what governs the direction in which bladder tumours grow. As it turns out, their collaboration may well have provided cancer research with a major new lead.

Tumour type is key

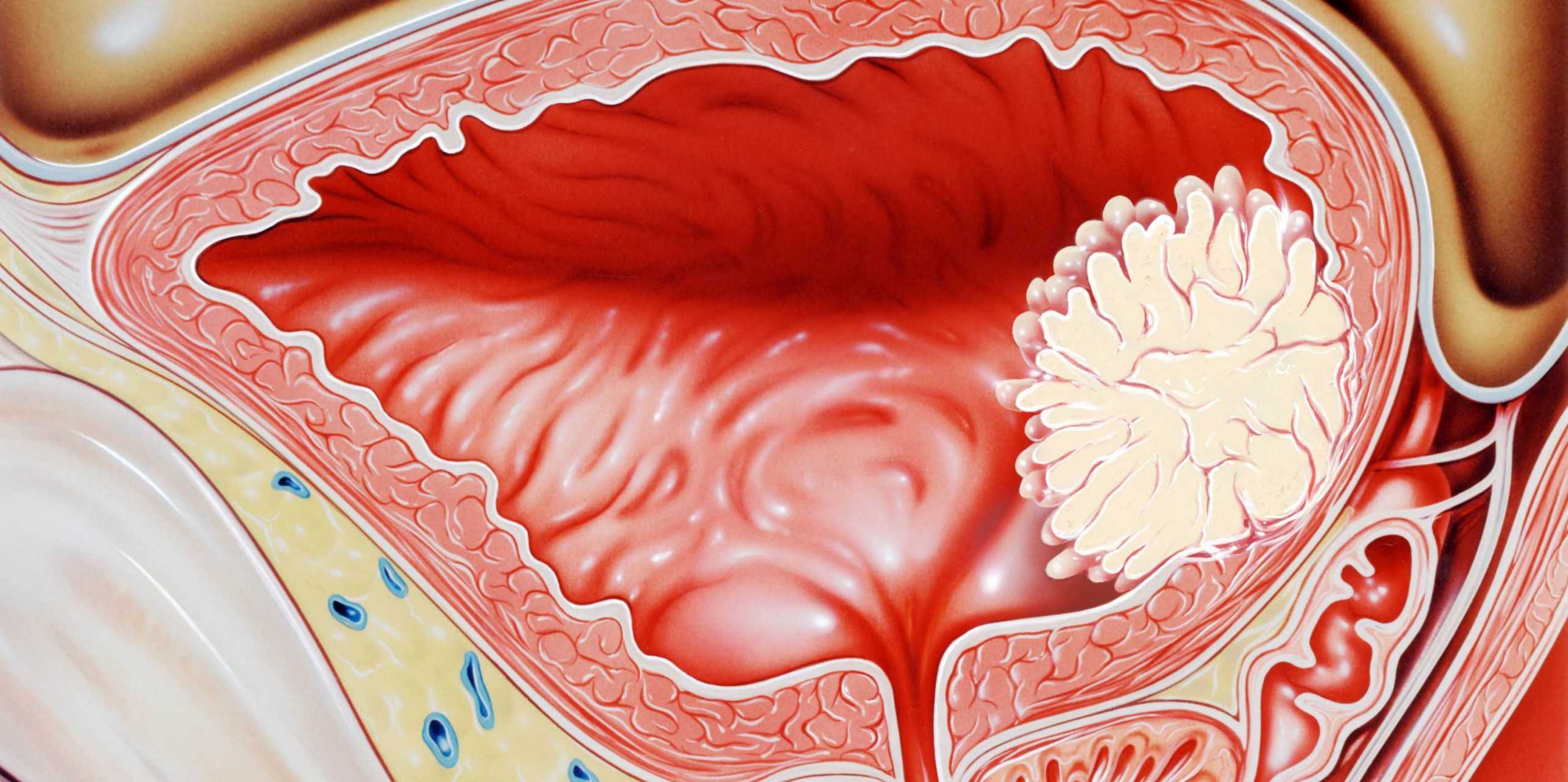

The direction in which a bladder tumour grows can play a key role in whether it proves malignant or benign. In turn, this also determines the course of treatment and the patient’s chances of survival.

One of the most common forms of bladder cancer is a papillary tumour. This has a slender, branch-like structure and grows from the bladder wall into the bladder cavity. It is a relatively benign form of bladder cancer that can be effectively treated in a minimally invasive procedure that involves scraping the tumour off the bladder wall.

Harder to treat is what doctors refer to as muscle-invasive bladder cancer, where the tumour grows not into the bladder cavity but rather into the deeper layers of the bladder wall. Access to blood and lymphatic vessels in those deeper layers facilitates the formation of metastases that can then spread through the body. In this case, the prognosis is much less favourable; frequently, the entire bladder must be surgically removed. It is known that these two forms of cancer differ genetically. However, these differences do not explain why one cancer type would grow into the inner layers of the bladder wall and the other grow out into the bladder cavity.

>> read on: find ETH News article at full-length.

“Cancer research needs to focus more closely on biomechanics and the chemical signalling pathways that affect it.”Dagmar Iber, Professor or Computational Biology, D-BSSE, ETH Zurich